Lawyers acting for clients imprisoned abroad need to navigate a complex web of interests. An estimated 2.5 million Canadians live outside Canada. In addition, Canadians make almost 50 million visits abroad each year. They travel or reside overseas to do business, study, visit family or vacation. Most find that their stay abroad is uneventful. Some, however, have the unexpected experience of being subjected to arbitrary and prolonged detention — and sometimes even torture.

When Canadians become enmeshed with problematic legal systems in foreign countries, they or their families back home in Canada often turn to a Canadian lawyer to help win their release. Canadian Lawyer explores the challenges that five lawyers recently faced when they acted for Canadians detained abroad.

Client: Cy Tokmakjian

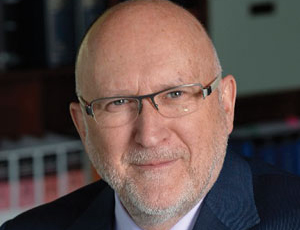

Lawyer: Barry Papazian

Country of detention: Cuba

Barry Papazian is a founding partner of the Toronto law firm Papazian Heisey Myers. A litigation specialist, he also does arbitration, domestically and internationally. He is the longtime lawyer of transport entrepreneur Cy Tokmakjian and his Concord, Ont.-based Tokmakjian Group.

Over 20 years, Tokmakjian had built one of the largest foreign-trade operations in Cuba, employing 200 people. He had even received a business award from Fidel Castro. But in September 2011, at age 71, the respected businessman suddenly became an accused criminal, swept up in the Communist regime’s anti-corruption drive. State security seized US$100 million of the company’s assets (in bank accounts, offices and inventory).

Following a two-week trial in June 2014 before the People’s Provincial Tribunal of Havana, Tokmakjian was convicted of bribery, damaging the Cuban economy, illicit economic activity, currency trafficking, fraud and tax evasion. He was sentenced in September 2014 to 15 years in prison. He was expelled to Canada in February 2015 following three years of detention.

Papazian says his client’s ordeal unfolded in slow motion. “Initially, he was only under house arrest. The seriousness of his situation didn’t click in for weeks.” Even after charges were laid, Tokmakjian believed the Cubans would realize they had made a mistake, says the lawyer. “Our job was to say, ‘yes, but we have to do all our homework.’”

Papazian says his client’s ordeal unfolded in slow motion. “Initially, he was only under house arrest. The seriousness of his situation didn’t click in for weeks.” Even after charges were laid, Tokmakjian believed the Cubans would realize they had made a mistake, says the lawyer. “Our job was to say, ‘yes, but we have to do all our homework.’”To do the homework, Papazian assembled a legal “dream team” within the first two months. He hired a Spanish expert on the Cuban legal system (which is derived from Spain’s system) at the international commercial law firm of Bird & Bird in Madrid. As local lawyers, he turned to a small Havana firm (one of a limited number allowed by the Cuban state to act for foreigners). He received advice from a former Cuban attorney general and an English-speaking commercial lawyer at the firm.

A Cuban working as a law clerk in Canada gave advice and translated for Papazian on the several trips that he made to Cuba. He consulted frequently with immigration lawyer Lorne Waldman, who discussed raising the case at the UN. “We didn’t pursue that for tactical reasons,” says Papazian. “We didn’t want to escalate matters.”

He also hired the litigation boutique of Lenczner Slaght Royce Smith Griffin LLP to launch a $200-million civil action in Ontario against the Cuban state. “It didn’t go very far; it was partially tactical, because Cuba’s sovereign immunity was an issue.”

Papazian also enlisted Navigator Ltd., the strategy firm, to guide him in Ottawa. “We needed to get to the right people at the highest level of foreign affairs,” he says. “Navigator said, ‘here’s how it works.’ I didn’t need influence; I needed channels of communication. I was extremely impressed by Foreign Affairs in every way, through the whole affair.”

He also hired a retired Mountie to run a check on Tokmakjian’s operations in Ontario to prove their bona fides. “He had no criminal record, no bankruptcies. Initially, we thought that would impress the Cubans.’’

Despite not being a criminal lawyer, Papazian felt comfortable being “fully involved” in his client’s defence, he says, because his business was a legitimate enterprise, not “an offshore tax situation.”

Initially, Papazian was hopeful that Tokmakjian’s release would come through the Cuban judicial process.

“Then I realized that it would require political collaboration, both here and in Cuba. If the Canadian legal system had applied, it would have been a civil rather than a criminal dispute. But the Cuban authorities applied the criminal law.”

The prosecution and the defence disagreed on the facts and the numbers. “The differences were huge,” says Papazian. But there were also procedural issues. No clear separation existed between the judges and the prosecution. Expert reports were filed, but the experts were not allowed to testify.

“It was not enough to say this was unfair,” he says. “That’s the system. You had to respect the system and work within it. There was an avenue to appeal the conviction, which we did. But the advice we received was that an appeal was much more restricted in Cuba than here in terms of potential success.”

Meanwhile, negotiations with Cuban officialdom were ongoing — both before and after the trial. “I tried to educate them as to why what happened was alright, from our perspective.” But the authorities had little understanding of basic Western economic concepts, according to Papazian. They calculated the corporate taxes owed based on revenues instead of profits. The cost of acquiring goods was not considered.

Ultimately, Papazian negotiated directly with Cuban officials from several ministries to gain his client’s freedom. He declines to discuss the negotiations, because Tokmakjian and his company had to sign a confidentiality agreement to secure his release. “I brought him back personally. I went there and stayed for five days and I wasn’t leaving until I came back with him.”

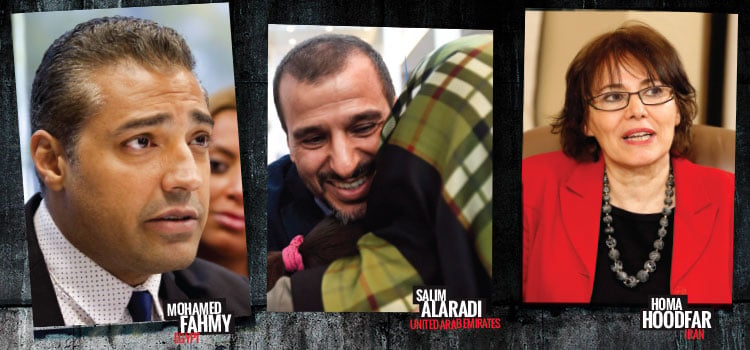

Client: Mohamed Fahmy

Lawyers: Gary Caroline and Joanna Gislason

Country of detention: Egypt

Gary Caroline and Joanna Gislason are partners at Vancouver-based Caroline + Gislason Lawyers LLP, and practise union-side labour law and human rights. In November, 2014, the pair was asked by a journalist friend to provide advice to someone imprisoned abroad. A few days later, they received a phone call from Mohamed Fahmy, speaking from a guarded hospital room in Cairo, Egypt.

Fahmy, the Cairo bureau chief for Al Jazeera’s English network and a dual Egyptian-Canadian citizen, had been arrested in December 2013 with two colleagues while reporting on the Arab Spring. He was serving a seven-year sentence on terrorism charges — principally, belonging to the Muslim Brotherhood, which the Egyptian government considered a terrorist organization.

Fahmy initially retained the Vancouver lawyers to file a lawsuit in B.C. Supreme Court against Al Jazeera, his former employer, seeking $100 million in damages. (They are no longer representing Fahmy in the civil action.)

Fahmy initially retained the Vancouver lawyers to file a lawsuit in B.C. Supreme Court against Al Jazeera, his former employer, seeking $100 million in damages. (They are no longer representing Fahmy in the civil action.)“We became more and more involved in trying to work out a strategy for dealing with his conviction and upcoming appeal,” says Caroline. “We worked to change the perception of Mohamed. His fundamental problem was that he was viewed as a member of the Muslim Brotherhood, and Al Jazeera was seen as an arm of Qatar, a state which supported the Brotherhood.”

Working with a well-connected Cairo lawyer, they tried to convince “the powers that be” — the government of Egyptian President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi — that Fahmy was neither a supporter nor a member of the Brotherhood. Fahmy did a series of interviews with the Egyptian media to influence local opinion-makers.

“At one point, I even appeared on an Egyptian TV talk show with him,” says Caroline. “Gradually, the media blitz softened the official view.”

Caroline travelled to Cairo for the appeal hearing, and found it an “eye-opening experience” to see how Egyptian lawyers had to shout over each other — and over a two-metre-high wall — to get the judges’ attention. “Prisoners were kept in a Plexiglas, sound-proof booth in the courtroom and couldn’t even hear their own lawyers.”

The appeal proved unsuccessful. On Aug. 29, 2015, Fahmy and his two colleagues were sentenced to three years in prison for broadcasting what the court described as “false news.”

Throughout this period, the Vancouver lawyers worked with a public relations firm in London to build support for Fahmy at the UN and in Europe. High-profile international human rights lawyer Amal Clooney “did great work in keeping the issue alive, primarily in Europe and the Gulf states,” says Caroline. “But I wouldn’t say that it was a tightly organized collaboration.”

On a volunteer basis, Caroline and Gislason organized a Canada-wide campaign for Fahmy. They courted the media and NGOs that defend freedom of expression. They mobilized 300 prominent Canadians to issue an open letter in support of Fahmy in September 2015. They enlisted the help of former prime minister Brian Mulroney.

All these efforts were intended to press Ottawa to become more active in seeking Fahmy’s release.

Caroline and Gislason had earlier established a channel with the Foreign Affairs Ministry, dealing mainly with consular officials. But they were underwhelmed by the diplomats’ mindset. “They took the attitude that they wouldn’t get their hands dirty figuring out ways in which President el-Sisi could save face in releasing Fahmy.”

As for the political echelon, Caroline doesn’t believe that then-prime minister Stephen Harper intervened in any meaningful way to try to secure Fahmy’s release. “The government saw no advantage in arguing on behalf of a dual citizen who was a Muslim,” he says dismissively.

But on Sept. 23, 2015, Fahmy and 100 other prisoners received a presidential pardon on the eve of Eid al-Adha, a holiday when pardons are traditionally granted. “El-Sisi apparently concluded,” says Caroline, “that incarcerating Fahmy was causing him more trouble than it was worth.”

Client: Salim Alaradi

Client: Salim Alaradi Lawyer: Paul Champ

Country of detention: United Arab Emirates

Paul Champ is an Ottawa-based litigator at Champ & Associates with a focus on human rights and labour law. He was hired in September 2015 by the family of Libyan-Canadian businessman Salim Alaradi, who had been arrested without charge in the United Arab Emirates in August 2014.

Alaradi’s family in Windsor, Ont. hired Champ after receiving evidence that Alaradi was tortured in the early months of his detention. Champ contacted the deputy minister of Foreign Affairs and the head of consular affairs. By mid-October 2015, consular officials were making weekly visits to Alaradi.

In countries with poor human rights records, says Champ, the most severe forms of abuse often occur within the first few days or weeks of custody. “As soon as the foreign government knows that there are people who are aware the person is in custody and are prepared to publicize it, you are minimizing the risk that abuse will take place.”

After spending 17 months in prison — the first three incommunicado — Alaradi was finally charged in January 2016 with funding and co-operating with two Libyan-based terrorist organizations. He was brought before a judge in the state security chamber of the Federal Supreme Court.

After spending 17 months in prison — the first three incommunicado — Alaradi was finally charged in January 2016 with funding and co-operating with two Libyan-based terrorist organizations. He was brought before a judge in the state security chamber of the Federal Supreme Court.At that time, Champ travelled to Abu Dhabi, where he met with the Canadian ambassador and the consular officials, as well as with Alaradi’s local lawyer. “I attempted to attend the court hearing, but the prosecutor ultimately barred me, and even family members, from the proceedings.” (Canada’s ambassador and a consular official were allowed to attend.)

Champ returned to Ottawa, but he continued to communicate with the UAE lawyer. “I wanted the Canadian government to be informed of the lack of access to counsel that Mr. Alaradi was experiencing. After being charged, he was allowed to meet with his counsel only twice.”

When a court order required that Alaradi be examined by a doctor, Champ pushed for the embassy and the local lawyer to request an independent physician. “At the end of the day, the UAE authorities disregarded all our requests and sent him to their own doctor.”

Champ had to tread carefully with the UAE lawyer. He was “immensely respectful of his status as the expert” on the Emirates’ legal process. In all their communications, Champ had to be alert to the likelihood that they were being monitored by the authorities. “Many Emirati lawyers who had worked on political cases had themselves been subsequently arrested. So there were very few lawyers who would even consider taking up this case. I had to be very respectful of his own safety.”

The terrorism-related charges against Alaradi were dropped in March 2016. He was then charged with the lesser offence of collecting donations without permission of the appropriate ministry and sending them to a foreign country.

The UAE Supreme Court ruled last May 30 that the evidence did not meet the charge and acquitted him. Alaradi was allowed to leave the country two days later.

A Canadian lawyer, says Champ, has to develop a political strategy as well as a legal strategy when a client is detained in an authoritarian state. That includes striking a “fine balance” between asserting his client’s rights to Foreign Affairs and recognizing that the department’s officials operate with wide discretion in those matters. “If you become too belligerent with Foreign Affairs, they can just disengage. Often, those consular officers are the only lifeline that you have to your client.” He says he maintained a positive relationship with the Canadian diplomats posted to the UAE.

Champ also advises reaching out to the foreign government’s diplomats in Canada as early as possible.

“You want to give them the sense that this is an individual who does have representation, who is prepared to make the case a political case perhaps. But you have to be tremendously respectful of those diplomats, even more so than of Canadian officials. You have to observe the diplomatic niceties.” (He declines to discuss any contact with the UAE’s ambassador to Ottawa.)

Client: Homa Hoodfar

Client: Homa Hoodfar Lawyer: Amanda Ghahremani

Country of detention: Iran

Amanda Ghahremani is a human rights lawyer with the Ottawa-based Canadian Centre for International Justice. Her aunt, retired Concordia University professor Homa Hoodfar, was on a visit to see family and do research in Iran last March when counter-espionage agents of the Revolutionary Guard detained her for questioning — the first of several interrogations — and seized her belongings. She was allowed to post bail but was prohibited from leaving Iran.

Thus began a seven-month ordeal, says Ghahremani, “in which my professional life collided with my personal life in an emotional high-stakes situation. I really had to take off my hat as a family member and put on my hat as a lawyer. I didn’t have room to be emotional; I had to be strategic.”

Hoodfar and Ghahremani agreed to talk by phone twice a day. They knew that if Hoodfar became unreachable, the situation had deteriorated. “We knew that bail might be revoked at any point,” says Ghahremani. “Alarm bells went off in June when she didn’t return home following a court hearing.”

Hoodfar and Ghahremani agreed to talk by phone twice a day. They knew that if Hoodfar became unreachable, the situation had deteriorated. “We knew that bail might be revoked at any point,” says Ghahremani. “Alarm bells went off in June when she didn’t return home following a court hearing.”Hoodfar was taken to Tehran’s notorious Evin Prison, which has a wing housing high-profile political detainees. The charges against her were not disclosed to the local lawyer she hired, and no trial date was announced. The Iranian press, however, reported that she was accused of “collaborating with a hostile government, propaganda against the state and ‘dabbling in feminism.’” (Hoodfar is an anthropologist who has done research on gender and Islam.)

Ghahremani, designated as her aunt’s lawyer in Canada, liaised with her family in Iran, but Hoodfar's family and Iranian lawyer had almost no access to her. At one stage, the presiding judge dismissed the local lawyer and replaced him — without Hoodfar’s consent — with one who was deemed acceptable to plead before the Revolutionary Court.

Stymied by Iran’s opaque judicial system, Ghahremani spearheaded an international academic and media campaign to win her aunt’s freedom. She enlisted academic and NGO support not only in Canada but in Pakistan, India, Indonesia, Brazil, Mexico and other countries with ties to Iran. She generated media coverage of her aunt’s plight. She also maintained close contacts with Canada’s Foreign Affairs Department as well as Ireland’s diplomats (her aunt also held Irish citizenship).

“I had a full plate already in a very demanding job at the CCIJ, and I had this international campaign that I was running, so in terms of the workload it was the most intense period of my life, with very little sleep.

But because my work was so closely related in terms of subject matter to the CCIJ’s types of cases — political prisoners, human rights violations — it allowed me almost to incorporate this work with some of the work I was doing for my job. I had understanding colleagues and supervisors.”

While the trans-national scope of the campaign leveraged Hoodfar’s support network, it also presented a challenge — making sure that everyone who wanted to help received correct information and respected the campaign strategy.

“If an organization, with all the best of intentions, used information [about Hoodfar] that was not accurate, that could eventually be used against her in the ongoing legal case,” says Ghahremani. “We were very careful to make sure incorrect information that could be detrimental to her case wasn’t circulating.”

Although Canada’s involvement in the case was hampered by its lack of diplomatic relations with Iran, Ghahremani forged a “very collaborative relationship” with the Foreign Ministry. The Canadian diplomats kept in close contact with her and “respected my level of knowledge and what I brought to the table. It felt like teamwork.”

A turning point came when Foreign Minister Stéphane Dion raised Hoodfar’s case in a meeting with his Iranian counterpart, Mohammad Javad Zarif, in mid-September in New York, on the sidelines of the UN General Assembly. The following week, after 112 days in detention, Hoodfar was released on humanitarian grounds, including poor health, and deported. Ghahremani accompanied her home from Oman, where Hoodfar spent the first few days recovering following her release.

Although Hoodfar’s freedom owed more to outside political pressure than to legal maneuver, Ghahremani considers it important for a Canadian lawyer to become involved when a Canadian’s rights are infringed on abroad.

“Most family members do not have a background in international human rights law or contacts with civil society,” she says. “They’re often distraught and don’t know where to start. They might not understand what the Canadian government can or cannot do. The lawyer ends up having to mediate between the stakeholders and managing the family. Lawyers have to take on the role of a counsellor and almost a caseworker.”

Editor's Note: The online version of this article has been corrected to state that The Canadian Centre for International Justice is based in Ottawa, not Montreal.

Ottawa