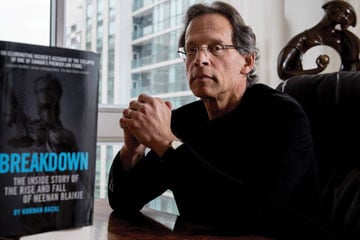

Three years after the collapse of the law firm he helped build, Norman Bacal reflects with his version of the inside story. Two pieces of framed artwork sit propped up against the wall next to Norman Bacal’s new desk at the Toronto offices of intellectual property firm Smart & Biggar Fetherstonaugh. The space is rather sparse — he hasn’t spent a lot of time here yet.

Two pieces of framed artwork sit propped up against the wall next to Norman Bacal’s new desk at the Toronto offices of intellectual property firm Smart & Biggar Fetherstonaugh. The space is rather sparse — he hasn’t spent a lot of time here yet.

Three years after the tumultuous collapse of Heenan Blaikie LLP and a stint as counsel at Dentons Canada, Bacal is taking on a new challenge for Smart & Biggar as co-chairman of IP strategy. His mission now is to help companies develop their IP portfolio and, in his words, wield it as “either a sword or a shield.” The idea is to give the C-suite level advice on how to better identify the value of an organization’s IP holdings.

It’s something the firm has been doing in Montreal, led in that city by managing partner François Guay. Bacal’s job is to recruit lawyers to put the same model in place for the Toronto market. The role at Smart & Biggar comes after taking time to write a book reflecting on his professional career and the ultimate meltdown of his professional life’s work — Heenan Blaikie.

It’s a self-reflective, personal account — he names names and says he’s “prepared to live with it.”

“I like to think I’ve been fair with everyone,” he says confidently, acknowledging that some players close to the drama may not like what he has to say. “Some will say I wasn’t hard enough on myself or wasn’t hard enough on Guy [Tremblay] and some from Toronto will say I wasn’t hard enough on Roy [Heenan] and others will say you should not have said anything bad about Roy.”

Three years ago, Bacal was in a very different state of mind sitting in a very different office on the 28th floor of the Bay Adelaide Centre. As he writes in Breakdown: The Inside Story of The Rise and Fall of Heenan Blaikie, on Feb. 14, 2014, he sat alone in his office, located on a floor of the Heenan office suites that were now “empty, stripped of any sign of life.”

It was nine days after the partners of Heenan Blaikie voted to dissolve the storied firm that had been home to prime ministers Pierre Trudeau and Jean Chrétien.

Bacal’s 16-year run as national co-managing partner ended in 2012, but he had returned at the 11th hour in a last-ditch effort to save the firm. “I failed. We failed. It was a stressful period for everyone,” he says.

Writing the book was “cathartic,” at least in the beginning stages of the process, Bacal explains. It was at the prompting of his wife Sharon that he took pen to paper.

“I remember having a discussion with my wife in the kitchen and she said, ‘You have a choice, either go for therapy’ — because I had a lot of anger — ‘or start writing it down.’” She handed him a book with blank pages.

Despite all he had accomplished as a lawyer in his career, he says he felt he had no “lasting legacy” to show to his kids after 34 years at Heenan Blaikie.

“I had no intention of writing a book when I started; it was just a complete catharsis. I wrote what is now the intro to the book and it hasn’t changed a lot,” he says of the chapter that starts the book. “It was pure emotion. Complete devastation. I can’t use a better word than that. I knew when I was finished writing it that I wasn’t prepared to confront what happened.”

The end result, released Feb. 28, is a “cut down” version of the original 900-page hand-written manuscript. He sent drafts to his kids to read and two chapters to a client, Bob Cooper, a Los Angeles film producer who told him to work on the “dramatic tension.”

Today, 600 pages remain on the cutting room floor. The first part of the book goes back to his student days and moves through the early days of the firm and all of its players — a chance, Bacal says, to take a look at his life.

Bacal, then an entertainment and tax lawyer from Montreal, arrived to set up the Toronto office at the end of June 1989. For the first six months, he says he would drive down Avenue Road and get a “rush of excitement” as he was heading to the office every morning. “That rush of excitement never died,” he says.

At its pinnacle, Heenan had about 600 lawyers and 1,300 staff from Quebec City to Vancouver and in its controversial Paris office.

“I remember feeling, this is something really special I have taken on,” he says. “I never thought it would fail. I had no idea where the experiment was going, but I always saw it as a great opportunity to put into practice my philosophies.

“I wanted a workplace where people would love to come to work every day and it wasn’t just about the lawyers — the receptionists, the hostesses — everybody counted,” he says. “There was a certain pride in being different that ultimately became our marketing advantage.”

So where did it all go wrong? He addresses the various factors in the book.

“The answer is complicated,” he says. “As much as this was a success story, there were incredible challenges. There were a number of moments along the spectrum where we thought this could come apart.”

Bacal says he never thought there was any problem he couldn’t, through conversation, solve.

“Did I know people were upset about the Paris office? Did I know people were upset about Jacques Bouchard? You couldn’t miss it, and I write about how the firm became polarized over how we were dealing with it,” he says.

Bouchard was the Montreal lawyer who was director of international business and centre of a National Post article about his connection to a lobbyist who was trying to obtain attack helicopters for an African country. He resigned in late 2011, but the firm was divided and perhaps overly distracted over how things were handled.

But never for a moment did Bacal think it was anything that couldn’t be solved when he returned to the helm in Toronto in the later part of 2013. He says he was optimistic to the end.

“I’m not sure if I’d call that period the worst six weeks of my life or the most interesting six weeks of my life — it was both. But at least I was in control again and I felt like I could influence the outcome,” he says.

“I think we would have gotten away with it if not for the terrible economy. Part of it was a perfect storm of bad events. With Kip [Daechsel] and Robert [Bonhomme], if they had been given a normal first year, they could have figured it out including how to work together. My ultimate conclusion was we put two excellent lawyers in place to run a business with no management experience and no leadership training.”

After all the analysis in the press and at the corridors of Bay Street, Bacal says he doesn’t think anyone has learned anything from what happened to Heenan Blaikie.

“My feeling is everyone has stuck their heads in the sand,” Bacal says without hesitation. “They go to sleep every night saying ‘I hope it doesn’t happen to us.’”

In the period before the firm officially dissolved, Bacal met with Heenan Blaikie’s bankers and they asked him, “Is there a lesson in this for us?” He told them every firm has a handful of lawyers who can serve as the collective barometer of how the firm is performing.

“Everyone knows who they are — they are not always the biggest billers, but you look at them and say, ‘This person is synonymous with this firm, and if that person leaves it’s not just a sign they wanted more money somewhere else. It’s a sign there might be something critically wrong.”

He is candid about the state of the legal profession.

“I think the market is very tough. This has been a continuing trend since 2009. It will continue unless and until the next era of greed is upon us. With Trump in the White House, I suppose anything is possible, but other than the huge transactions or bet-the-farm litigation, clients are much more conscious about costs, which means much more pressure,” he says.

Bacal won’t speculate on whether other Canadian firms may be close to the same fate as befell Heenan Blaikie. However, unlike three years ago when Heenan was bleeding lawyers fleeing the ship for what they thought were greener pastures, there are fewer places today for associates or partners to go.

“It doesn’t matter how badly you’re doing; if there’s nowhere to go, no one is going to leave; you’ll just earn less money,” he says. “You downsize, you do it quietly and if you’re good at that you can survive anything, even if people aren’t happy. My guess is there are a lot of unhappy people out there, but they aren’t leaving. Lawyers, just by nature we are very conservative — we don’t like change; we would rather put up with a bad situation.”

Bacal believes he also has some wisdom to share with new lawyers. Through his relationship with André Bacchus, assistant director of the work placement office at Ryerson University’s Law Practice Program, he plans to do some speaking to LPP candidates.

“Young lawyers and students need to think about what they want to get out of the profession. It isn’t about being part of a big law firm anymore. I think they need to ask themselves strategically, ‘What’s best for my career?’ For some, it will be to put in three to five years and find a great in-house job and see that period as an investment. For many, I would say find what interests you and follow it,” he says.

For now, Bacal is leaving non-fiction and moving to his new obsession — writing a murder mystery series including a “modern-day Othello” where perhaps not surprisingly a lawyer dies.

“In fiction, anything can happen,” he says.

Which may also be the case in big law.