New book details legacy of "arguably one of the most effective judges the court has had"

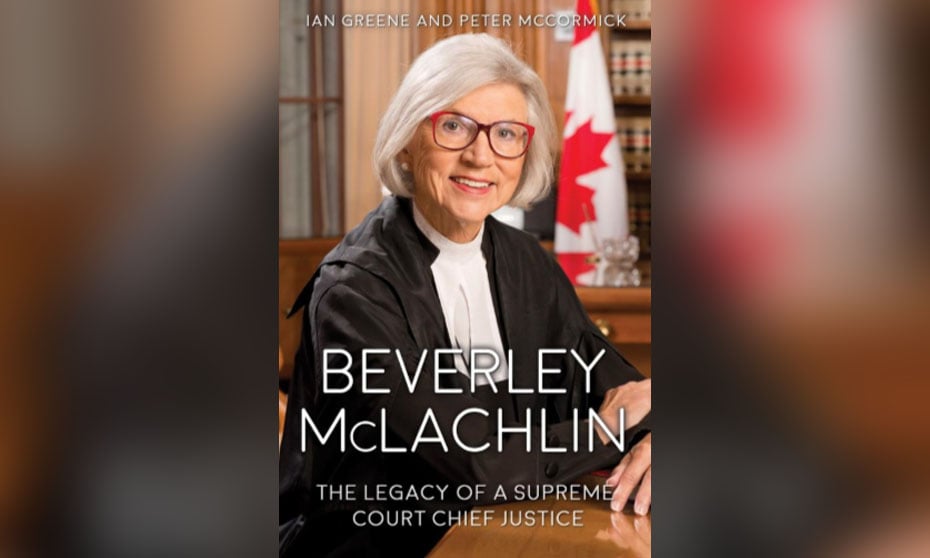

A biography released today of former Chief Justice of Canada Beverley McLachlin meticulously documents her life, career, judicial decisions, and showdowns – at least, the noted public altercation in 2014 with Prime Minister Stephen Harper.

Beverley McLachlin: the Legacy of a Supreme Court Chief Justice opens by describing the first female and longest-service chief justice of the Supreme Court of Canada as “arguably one of the most effective judges the court has had in terms of the advancement of the rule of law and human rights, clarity of writing, leadership and the promotion of collegiality.”

Legal academics Ian Greene and Peter McCormick interviewed McLachlin for this biography; like her, they both grew up in rural Alberta (and later also attended the University of Alberta), and this is where the story begins: where in 1943 McLachlin was born Beverley Marian Gietz, the first of five children to German-speaking immigrant parents who came to farm “on a ranch nestled in the foothills of the Rocky Mountains west of Pincher Creek, Alberta.”

Working her way through law school, private practice, teaching at UBC’s law school, and serving on the bench in B.C. before her appointment to the Supreme Court of Canada in 1989, she was elevated to chief justice in 2000, where the authors credit her with turning “a divisive court into one of the most collegial and reflective institutions of its type in the world, and in contributing significantly to decisions concerning assisted dying, prostitution, safe injection sites, prisoners’ voting rights, Canada’s obligations to child soldiers and Aboriginal rights, among other issues.”

Faced with an attack by then-Prime Minister Stephen Harper when she attempted to warn him of a potential problem with his pick to fill one of the three Quebec seats on the Supreme Court, “she never lost her cool in defending herself, the Canadian judicial system and the rule of law,” the authors write.

The central legal issue concerned how the Canadian Constitution defines the qualifications for judges appointed to the Supreme Court from Quebec, of whom there must always be three. These judges are in particular expected to provide expertise in Quebec civil law. The Supreme Court Act clarifies that “from Quebec” can mean from the bench of the Quebec Court of Appeal; from the bench of the Quebec Superior Court; or a member of the Quebec Bar with 10 years of experience.

McLachlin was concerned that Harper’s choice of Marc Nadon, a Federal Court judge, for the Supreme Court vacancy did not meet the requirement of “from Quebec,” and attempted to notify him of the potential constitutional issue in July 2013. (A Federal Court judge had never before been appointed to fill a Quebec seat on the Supreme Court.) On May 1, 2014, Harper responded by issuing “a press release accusing Chief Justice McLachlin of improper behaviour” and of “lobbying” – a violation of the constitutional buffers between the government and the judiciary. It was the first time that a Canadian prime minister had publicly criticized a chief justice.

The authors note that, beginning in 2008, the Harper government had lost a series of cases in the Supreme Court, and hoped to introduce a judge more sympathetic to Conservative policy.

In July 2013, McLachlin had also conveyed her concern to Justice Minister Peter MacKay, but in decided in the end not to contact the prime minister directly.

A parliamentary selection committee included Nadon’s name in its list of candidates, Harper announced Nadon as his choice, and Nadon was sworn in as a Supreme Court justice on October 7, 2013. But the appointment was challenged by a Toronto lawyer, and 10 days after the swearing-in, by the government of Quebec. Just five days after that, the federal government moved to amend the Supreme Court Act as part of an omnibus bill.

In the end, the issue went to the Supreme Court, where a majority decision that included the two remaining Quebec judges found that Nadon’s appointment was invalid, as were the proposed amendments to the Supreme Court Act. In April, the Harper government lost another reference: the Senate Reference. Harper was “enraged” and a story was leaked to the media that Chief Justice McLachlin had “lobbied against the appointment of Marc Nadon,” with the PM’s press release issue that same day: May 1, 2014.

McLachlin issued her own release the following day denying any communication between herself and the government “regarding any case before the courts,” and setting out the facts, including her wish to ensure that the government “was aware of the eligibility issue.”

There was more pushback from Harper on May 2, and the Canadian legal community reacted swiftly, with more than 650 lawyers – including 11 past presidents of the Canadian Bar Association and the Council of Canadian Law Deans -- signing and publishing a statement in support of McLachlin. Her backers also included four former prime ministers, Conservative and Liberal alike (Clark and Mulroney, Chrétien and Martin).

“The fact that a prime minister so blatantly violated the constitutional convention of judicial independence indicated that he either disagreed with the principle of did not understand it,” the authors write, adding that McLachlin’s “fierce defence of the Supreme Court’s reputation and of judicial independence generally make up an important part of her enduring legacy.”

Beverley McLachlin: the Legacy of a Supreme Court Chief Justice is written in an accessible style and will be of interest not only to jurists, but to readers interested in how case law is made; the workings of the Supreme Court of Canada and the inter-workings between government and judiciary; and in the life, career and legacy of a remarkable woman.