Courts are implementing video and telephone conferencing as well as remote filing

In response to COVID-19, criminal trials are being postponed across Canada and courts are employing remote filing and telephone and video-conferencing to proceed in urgent matters. Some criminal lawyers say the courts being forced to rely on technology may be a silver lining in the pandemic.

Vancouver criminal-defence lawyer Sarah Leamon says COVID-19 should serve as an impetus for overdue technological progress in the criminal justice system.

“If there's one good takeaway from what's going to happen here, I think it will be to move the criminal justice system along to embrace more technology so that we are being more efficient with our resources and our time,” she says.

The COVID-19 pandemic has largely put the brakes on criminal trials. Over the past two weeks, courts across Canada have announced the adjournment of all non-urgent matters. Restrictions vary from province to province, but generally only proceedings involving an accused in custody – for bail hearings, preliminary inquiries, and youth criminal sentence reviews – are moving ahead, with participants engaged via telephone or video conference where possible.

“The decision that's been made by the Ontario Provincial Court, and the provincial courts throughout Canada, is that they're banning any sort of out-of-custody matters for 10 weeks, and then they're going to take stock of the situation at the 10-week mark,” says Calgary lawyer Jeinis Patel of Kay Patel Mahoney Criminal Defence Lawyers.

Leamon practises in Vancouver but has clients in the suburbs. She says that in normal times her firm’s lawyers and articling students often spend the bulk of their day in a car, driving between courthouses to make “nominal appearances.” When the technology is available to save the trip it would save time and resources, she says.

“That might also help us with the delay issues that plague the criminal justice system,” she says.

Though Patel says the courts should have embraced more technology long ago, there is a statutory sticking point to conducting criminal trials remotely. “Archaic” provisions in the Criminal Code prevent some trials from proceeding via telephone or video conferencing, he says.

“With the scale of sophistication of the technology … I don’t understand it,” he says.

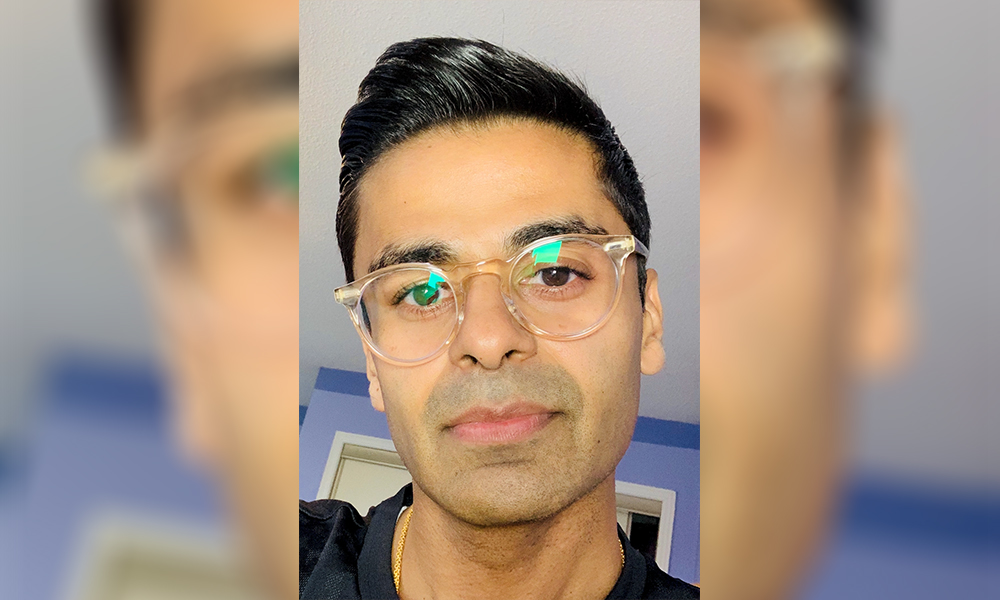

Jeinis Patel of Kay Patel Mahoney – Criminal Defence Lawyers

Jeinis Patel of Kay Patel Mahoney – Criminal Defence Lawyers

Section 650 (1.1) of the Criminal Code, which deals with indictable trials, contains a rule that requires that when evidence is taken, the accused must be in the courtroom.

“That would imply that a person has to be physically present at that time, which would, in my view, … to a degree, thwart the prospects of a completely online trial where everything is done outside of court,” Patel says.

The same is not true for summary trials, for which the Code allows the accused person to appear by video, he adds.

Leamon says the room for technological advancement exists in all areas of law. Taking signatures for affidavits and statutory declarations can be done remotely, she says; and the chief justice of British Columbia recently released guidelines for witnessing signatures over Skype.

“For people who are more marginalized, the ability to have your lawyer, who lives in a different jurisdiction than you, sign paperwork is enormously beneficial to them,” says Leamon.