Find your own voice and style, and don’t let self-doubt hold you back, panellists advise

This year’s Canadian Law Awards featured a panel discussion on the topic “How Today’s Leaders are Redefining Success and Breaking New Boundaries.” The consensus of the all-female panel? While much progress has been made in the advancement of women in the legal profession, there is much still to do. And young people entering the profession today were advised to find their own voice, and not let self-doubt hold them back.

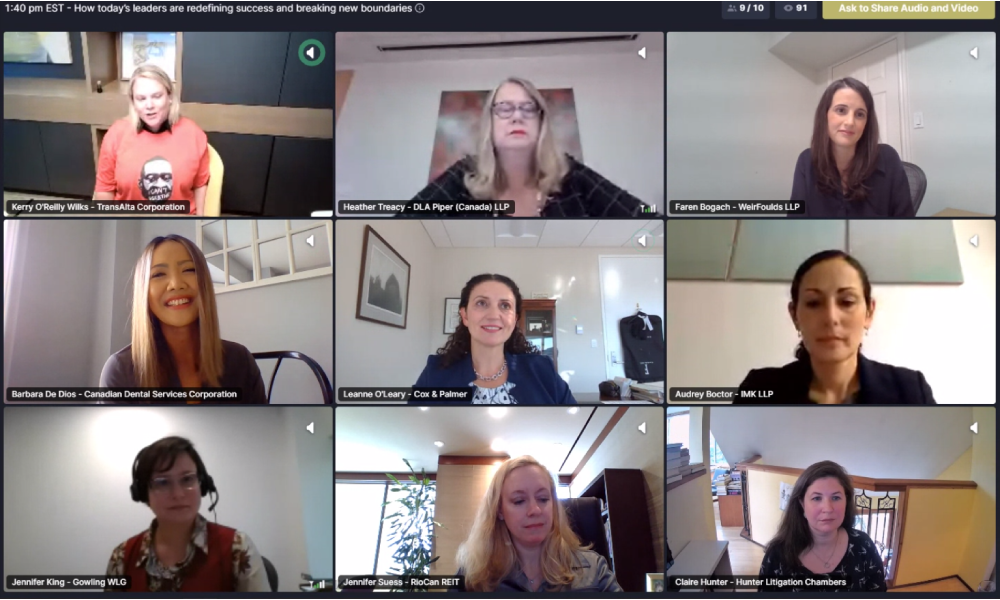

Eight female lawyers from across Canada, in private practice and in-house, participated in the Gowling WLG Award for Woman of the Year Panel moderated by Gowlings partner Jennifer King.

“At this particular moment in history, it's easy to be frustrated by the pace of change,” said Claire Hunter, counsel in Hunter Litigation Chambers in Vancouver. “But I hope that the next generation of leaders will draw some strength from the advances that have been made in a single generation,” she said, recalling a recent conversation with her mother, who had graduated from law school in 1975, when there were very few female lawyers in British Columbia.

There were no female judges on the B.C. Superior Courts, “and my mother's generation did hard work of expanding the imagination of the profession as to how lawyers should look, should sound, should act,” said Hunter. “They answered interview questions about whether they planned to have a family or to practise law, and they entered a profession where they were expected to act like their male colleagues.”

Many among them worked to establish parental leave policies, flexible work arrangements, and to bring on and mentor other young lawyers who did not fit the traditional mould. By the time Hunter started interviewing for legal jobs in 2001, “that shift in imagination was reflected in policies on diversity inclusion, on parental leave and flexible work arrangements.” There were female judges at all levels of courts, and Beverley McLachlin had become the chief justice of Canada the year before. And Hunter added that she was supported by the lawyers that she juniored for, who were all men.

One good indicator of the leadership role of women in the profession is the number of women in judicial positions, said Leanne O'Leary, managing partner of Cox & Palmer LLP and based in St. John’s.

Across the provinces, she said, approximately 40 per cent of the chief justices at the supreme court level are women, and 30 per cent at the appellate level, and Canada had a female chief justice until recently. “I think those are all markers and indicators of significant leadership that we have in this profession; and it's a great model as we move forward.”

In addition to greater numbers, the goalposts have moved “on the ability of women in the profession to come into the leadership roles with their own voice, bringing their own leadership style to the table, and without that expectation or sense of obligation that they need to manage like a man would manage or they need to think like a man would do so,” O’Leary said.

“I think that it is [through] the ability of us to be women and to be the leaders that we will measure our true progress.“

Heather Treacy, a partner in DLA Piper (Canada) LLP, noted that when she became managing partner of its Calgary office in 2013 she was typically the only woman at managing partner events. When she left that position in 2019 to join her firm's national executive committee, she estimated that 20 per cent of the managing partners at those same events were women.

That said, “what is really needed in order to ensure momentum and further progress is that firms have champions for women, and that the senior leadership in the firm creates opportunities for women,” Treacy said. “There has to be buy-in from the top. We know that's the right thing to do, but it also makes economic sense as well.”

Panellists agreed that there was more work to be done.

Audrey Boctor, a litigation partner in IMK LLP in Montreal, cited an American Bar Association survey in which female respondents reported being treated differently than their male colleagues.

“There are differences in how women are evaluated, in the constant feeling of needing to still prove oneself, even though one has achieved the position of leadership, [and] being judged more harshly when things don't go well,” Boctor said. These same observations were made by Canadian female first ministers in the recent podcast series No Second Chances, she noted. “So I think there's a lot more to do.”

For the next generation, mentorship and getting involved in programs that support female lawyers and build leadership skills are essential, said Barbara Dos Dios, corporate counsel for Canadian Dental Services Corp., as is communicating one’s ideas about change to management. “Find a mentor, push away self-doubt and start now.”

“I would tell a young lawyer, if you aren't too uncomfortable in what you're doing, then you're not growing,” said Kerry O'Reilly Wilks, chief officer of Legal, Regulatory and External Affairs for TransAlta Corporation. “You need to decide where you want to go and make a game plan and … think outside the box.”

Public speaking and managing people are both important to career development, said Jennifer Suess, senior vice-president, general counsel and corporate secretary of RioCan Real Estate Investment Trust.

“You need to be deliberate and very aware of where you're uncomfortable, … and then push yourself to do panels, push yourself to get out there and get on committees,” Suess said. “There's so many amazing opportunities now to do so many things. Don't just sit back and wait … Find the path that resonates with you and just go for it.”

Faren Bogach, a partner and litigator in WeirFoulds LLP in Toronto, noted the awareness that Black Lives Matter and other social movements have brought to the need for diversity, which “is starting to get some real traction with firms.

“There is mounting external pressure to have diversity on a panel,” Bogach said. “I'm seeing creative ideas from our young women,” and firms embracing this change.