Medical malpractice lawyers offer varying views about whether the CMPA has too much power

Malpractice lawyer Paul Harte says in a typical year, he gets about 1,000 calls from potential clients who want his firm to take on their case after they feel their physician treated them negligently. Harte might take on only about 25 of those cases, based on his assessment of how much it would take to litigate the case, whether it is winnable and what the award could be.

The reaction from those who have their cases turned down, he says, is something along the lines of “are you kidding me? The doctor made a mistake, and you’re telling me you can’t help me — how can this be possible?” It’s a difficult conversation to have, Harte admits, and certainly embitters these clients against the entire medical service.

Paul Harte

And the reason for this, Harte says, is at least partly because of a powerful non-profit organization, the Canadian Medical Protective Association, with vast funds (about $5 billion in assets) at its disposal, most of it linked to government sources. The money is used to settle cases, pay awards, and defend health professionals accused of negligence. While doctors pay dues to be members of the CMPA, provinces pay the physicians back; in some cases, up to 90 per cent, less a small fee.

Harte says this situation leaves “zero incentive” for the CMPA to reduce costs and be more efficient in protecting doctors, leading to a “scorched-earth” strategy.

An Ontario Superior Court judge also used the same analogy as Harte when he commented in a 2008 ruling, Frazer v. Haukioja, that the CMPA-funded lawyers in a suit against an emergency doctor had pursued a “scorched-earth policy.” In the ruling, the judge wrote that the defence put the plaintiffs to the test of establishing virtually all of their claims on all issues of damages and liability, “and making the trial — at 20 days — needlessly long.” The patient was ultimately successful, though, with an award of $1.9 million, as well as plaintiff fees and disbursement costs of almost $930,000.

The ability of the CMPA to vigorously defend doctors accused of malpractice means the threshold for taking on a case is high, says Harte, who worked on the defence side for the association before becoming a medical malpractice plaintiff lawyer. “It is just not always economically viable to take on a doctor. It also creates a situation where the number of suits brought against doctors is lower than what it could be, and those cases that are litigated arguably produce better results for defendant doctors.”

While the threshold varies from lawyer to lawyer, Harte says somewhere around $250,000 is a typical settlement or award amount that makes a case worth taking on.

An example of one “economically unviable” case that Harte turned down involved a 22-year-old waiter with a benign tumour in his rib. After the operation, a problem occurred, allegedly because of a medical error, and the man had to have another operation. However, “even though it’s a painful surgery, and the fellow had to take more time off, maybe the case is worth $20,000,” Harte says. Here is a case “where I think an error was clearly made,” he says, but he turned it down because the cost of litigating would far outweigh the award, given the CMPA’s defence-of-doctors mandate.

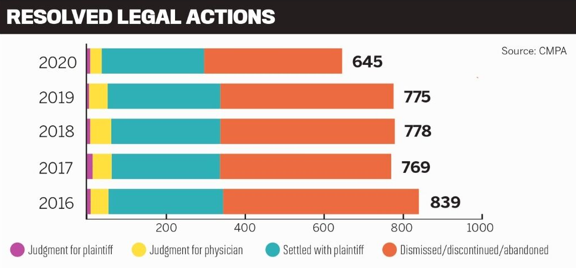

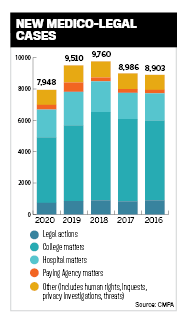

Harte says that because of how the CMPA works, there has been a steady reduction in legal actions. Over the past five years, the number of new legal actions has dropped every year. In 2016 there were 891 new legal actions which went down to 732 in 2020. In 2016, there were 839 resolved legal actions, of which 495 were dismissed, discontinued or abandoned and 290 were settled: 45 judgements in favour of the physician and nine for the plaintiff. Of 645 resolved legal actions in 2020, 349 were dismissed, discontinued or abandoned and 259 were settled with the plaintiff, while 29 judgements were for the physician and eight for the plaintiff.

“It’s unlikely that there are fewer mistakes being made,” says Harte. “In fact, as we get more complicated medicine and more multi-disciplinary teams, the error rate is likely higher, not lower. What’s happening is that, because of the impediments to suing, all kinds of meritorious claims are going without compensation.”

The CMPA takes issue with arguments that Harte and other lawyers use to criticize the CMPA. Dr. Todd Watkins, associate CEO with the CMPA, says the organization’s mandate is to “protect the professional integrity of physicians and promote safe medical care in Canada.” Legal actions naturally call into question the integrity and reputation of the physician, he says, so allegations that question the physician’s medical judgment and expertise “can be devastating to their future ability to practice, regardless of any monetary value.”

Accordingly, says Watkins, when a patient initiates a claim against a physician member, the role of the CMPA is to assist the member in their defence if the care provided is medically defensible. “If the standard of care was met, the integrity and reputation of the member will be defended against the claim. However, if experts conclude the standard of care was not met, and this failure harmed the patient, appropriate financial compensation to the injured patient or the patient’s family or estate will be provided.”

As for the “war chest” the CMPA has, Watkins says it is an unfair assessment that doesn’t reflect the association’s approach to defending physicians or that it is structured with sufficient funds to compensate those who have received negligent care, now and in the future. “The CMPA is committed to ensuring we can compensate patients and their families appropriately and in an amount that reflects their long-term care needs,” he says. And unlike an insurance company, the CMPA is not restricted by pre-set compensation amounts or capped damages.

There are also plaintiff lawyers who don’t share Harte’s position. Richard Halpern, a malpractice lawyer with Gluckstein Lawyers, says “the fact that most plaintiffs lose their case against doctors is not an indication of a problem with the system, it’s an indication the problem is with their case.

“Judges don’t care how much money the CMPA has. If you go to trial against a doctor, and you lose the case, it’s [for] one of two reasons. Number one, your case didn’t have merit to begin with. Or number two, your lawyer didn’t handle the case properly.”

Richard Halpern

Ryan Breedon, who spent several years working for a law firm that was counsel to the CMPA in Ontario, adds that medical malpractice is difficult to litigate and often expensive. “It’s more about the law and the standard of proof that a plaintiff has to meet. The approach of the CMPA is that if a case is considered defensible, they will defend it, and if not, it will be settled. I don’t take issue with that.”

Breedon adds that smaller cases often don’t get pursued because of how the system is set up. However, the flip side of the coin is that serious cases involving catastrophic injury are given settlements or awards to meet their care needs better. Unlike insurance for vehicle accidents, there are no limits on medical malpractice cases.

The question of reputation is important for members of the medical profession, says Breedon, as it can have lasting consequences. He says that no procedure or treatment has a 100 per cent chance of success, and someone will inevitably be on the wrong side of the statistics. “These cases tend to be litigated in the communities where doctors live and work, and it’s not like a car accident with insurance, which will be settled.”

Halpern agrees, saying doctors are entitled to protect their reputation. He adds that what a patient sees as malpractice in many cases is simply a bad outcome despite a proper standard of care. And often, there is an underlying health issue with the patient, or the nature of the procedure comes with some known risks that the patient should have agreed to through informed consent.

“Every procedure carries risk. Not all bad outcomes are due to bad care, but some are,” Halpern says. The role of the malpractice lawyer is to tease out which are which.

However, Harte says the system under the CMPA works on the “archaic view that doctors never make mistakes,” and too much time is spent defending that view. The premise is, “if you admit to any kind of an error, that means that you’re inherently not a good doctor and your reputation takes a hit,” he says. That isn’t the case, he adds — “even excellent doctors make mistakes.”

When it comes to government reimbursement of most of the fees doctors pay to be part of the CMPA, Harte says this goes back to the rise of medical malpractice premiums in the 1980s, particularly in the United States, and the fear that the same thing might happen here. This resulted in medical associations arguing that this could mean losing doctors, so they struck an agreement with the provinces outlining how the government would reimburse any increase in fees beyond a certain base level. According to Harte, “Now, 30 years later, every specialty pays a different premium, but in general, 90 per cent of the premium is reimbursed because that base rate has even been increased by inflation.”

Halpern argues that subsidizing doctors on malpractice fees is a fair trade-off for Canada’s universal healthcare system. “Because of that, the system has capped earnings for doctors. They are told what to charge for a procedure,” he says, arguing that doctors in Canada are probably underpaid relative to counterparts elsewhere. “One of the things doctors were able to negotiate was partial subsidization of their premiums for malpractice. I think that’s completely appropriate.”

The CMPA’s Watkins contends the group is not subsidized and does not receive any funding from governments or taxpayers. “The CMPA collects membership fees from doctors each year, and these funds held are used to compensate patients injured as a result of negligent medical care [or fault in Quebec], support members facing medico-legal difficulties and advance safe medical care.”

Instead of paying doctors more money, he says, governments reimburse doctors directly for a portion of their CMPA fees. “The amount of reimbursement varies by province or territory depending on the specific provincial-territorial agreement in place. These agreements are negotiated by provincial or territorial medical associations or federations. The CMPA is not a party to these negotiations or agreements.”

The other challenge for malpractice plaintiffs is finding expert witnesses to testify whether a physician was negligent and if poor performance hurt the patient. Harte says most cases rest on such evidence. Plaintiff lawyers say it’s challenging to find someone willing to testify against a colleague, and a culture of silence and “circling the wagons” exist.

However, Halpern at Gluckstein says too much is made of this argument. He says it is true that many doctors are hesitant to criticize their colleagues, “but I have been doing this more than three decades now, and I’ve never had a case where I couldn’t find an expert who was prepared to give me an objective opinion.”

“It may be challenging for us to find experts who are prepared to testify. The fact is that there are always highly qualified, very competent experts who will look at your case and provide you with an objective opinion.”

Breedon agrees, saying the inability to find experts to testify for the plaintiff is “overblown.”

As for solutions to some of the challenges of dealing with malpractice cases, especially at the lower end of the potential award or settlement spectrum, they range from better education and training to no-fault insurance models used for vehicle accident claims.

Says Harte: “How do you fix the problem? The answer is changing the mandate of the CMPA from protecting doctors’ professional reputations to compensating victims of medical mistakes at the lowest reasonable cost.” He says the current system leads to a huge dichotomy between winners and losers — with the most serious cases of proven malpractice well-compensated while cases of lesser economic value are shut out of the system.

A more inclusive system would lead to greater economic dealing of more cases, which would mean there would be more lawyers to represent malpractice litigants. “We need to figure out a way to reduce transaction costs. And one of the ways you do that is by settling cases quickly by identifying any case that has to be resolved and settling it for a fair dollar.”

Breedon says the concept behind finding ways to make it more economical to deal with the cases below is good in theory. Still, he worries that such a system might mean less for the most catastrophic cases — where large settlements can impact quality of life.

Halpern says preserving the tort system for medical malpractice cases is crucial, explaining that versions of no-fault insurance in other countries have not worked well. “The notion that there might be a correlation between no-fault medical compensation and improved patient safety is absurd.”

Indeed, eliminating the accountability and deterrent effect of the tort system means it is likely to put more patients at risk, he says. As part of the Holland group, which includes CMPA lawyers and plaintiff lawyers, to look at possible reforms, Halpern says any potential changes would not undermine the tort system.

“We encourage best practices, both on the defense side and on the plaintiff side. And what that means is that we encourage lawyers who engage in this work to carefully evaluate cases early to determine early on whether or not the standard of care or causation has been met ... and then to proceed only with cases where you can establish that there is merit.”