Current court system often been a barrier to justice, rather than a 'critical tool in pursuit of the truth'

The Canadian justice system must recognize the existence of the many Indigenous legal orders in Canada, reconciling them with common law and current legal protocols, delegates to a Canadian Institute for the Administration of Justice's conference on Indigenous peoples and the law were told.

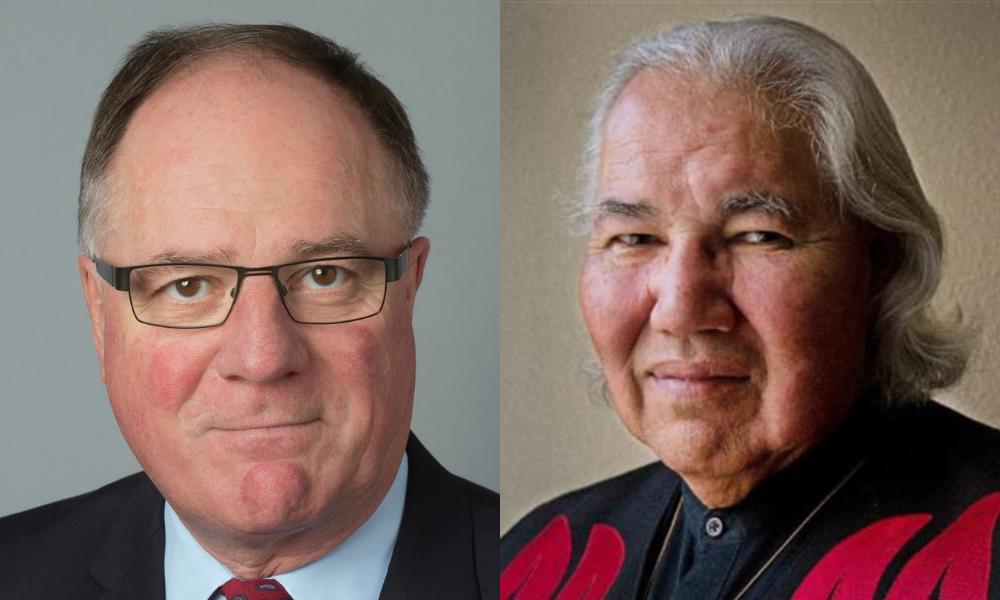

“Preservation of distinctive Indigenous culture and government is critical, not only for their survival, dignity, and well being of Indigenous peoples. . . but also as a valuable part of state identity,” said Chief Justice Robert Bauman of the British Columbia Court of Appeal and Court of Appeal of Yukon.

He made his comments in the opening session of the 45th annual conference, held virtually and in-person in Vancouver. “As we find space for Indigenous legal orders, we must look to Indigenous peoples to determine what that space will look like.” He added that a process of reconciliation, including legal reconciliation, must be prioritized.

In embracing an approach of reconciliation with Indigenous peoples, including legal reconciliation, Bauman said, “our assumptions about law and equity must be supplemented, and maybe in some circumstances be supplanted.” Bauman noted that the Supreme Court of Canada recognized self-determination as a right of Indigenous peoples to pursue their political, economic, social and cultural goals.

He added: “We must hold space for hard conversations and be willing to be wrong. If there’s anything that the last 200 years of Canadian Indigenous relations has taught us, is that our jealous need for control is destructive. . .. Now is time to do what we should have done when we arrived here, as uninvited guests, and demonstrate that we care enough to discover and learn and to act responsibly within the matrix of Indigenous customs, traditions, and protocols. Now is the time for humility.”

Justice Bauman pointed out he is not Indigenous or a scholar of Indigenous legal orders but is among the “target audience” that Indigenous people must address. “One of the sites where law is recognized . . . is the courtroom of a Canadian legal system. So, I am someone who some of you [must] attempt to speak to, to educate and to patiently bring along.”

While he acknowledged that it is his “responsibility to educate,” he said, “the only progress I’ve made is through the generous sharing and teaching from Indigenous people and scholars offering their knowledge and experiences with me.”

Chief Justice Bauman also said that the adversarial litigation process “has in many cases failed Indigenous peoples as a suitable forum for reconciliation.”

For Indigenous peoples, “the court system has often been a barrier to justice, rather than a critical tool in pursuit of the truth,” he said, and this attitude has suppressed truth and deterred reconciliation. "It is this history and current reality that gives urgency to our duty to act.”

Retired judge and Canadian senator Murray Sinclair was also among the speakers on the first day of the three-day conference, drawing on his experiences as a provincial court and Court of Queen’s Bench judge in Manitoba. He also served as chairman, from 2009 to 2015, of the Indian Residential School Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

Sinclair, who grew up on the former St. Peter’s Indian Reserve in the Selkirk area north of Winnipeg, noted that the current mainstream systems of justice would likely be “very resistant” to another justice entity “taking over” from what it is currently doing. He also admitted that there are challenges with integrating Indigenous justice into a provincial and federal court system, “but I think we’re far better along the road of understanding,” he said.

Sinclair added: “Indigenous people for thousands of years have been managing their own lives without the . . . direction or support or assistance of non-Indigenous people. And we need to recognize that the extent [to which those systems have become] unused is because of the . . . negative influence of the existing Canadian legal system and English legal principles, and the attitude of those practitioners who are in charge of those systems have had to Indigenous law and Indigenous institutions.”

The former judge and senator also said that Indigenous peoples often suffer abuse when exercising their rights. Sinclair pointed to the fishing dispute in Nova Scotia, with Indigenous property being destroyed by non-Indigenous fishermen. “And we see the police standing aside . . .and say ‘well, it’s just a difference of opinion.’”

The result of such mistreatment, Sinclair said, is that Indigenous youth are getting increasingly frustrated.

“So, we need to understand that until we redress those conflicts and redress those ways of thinking, we are going to augment the level of frustration that young Indigenous people are facing, and they will be . . . educated and better capable of leading than . . . in the past,” Sinclair said. “We have a lot of work to do to change the direction of what we have been doing . . . or else we will be setting ourselves up for more significant confrontations than we have in the past.”