Panel members analysed the great resignation, cultural shifts and lawyers' new priorities

As the great resignation continues to impact companies, industry leaders at the Canadian Lawyer LegalTech Summit examined the changing landscape for law firms and lawyers and the impact on business and technology innovation.

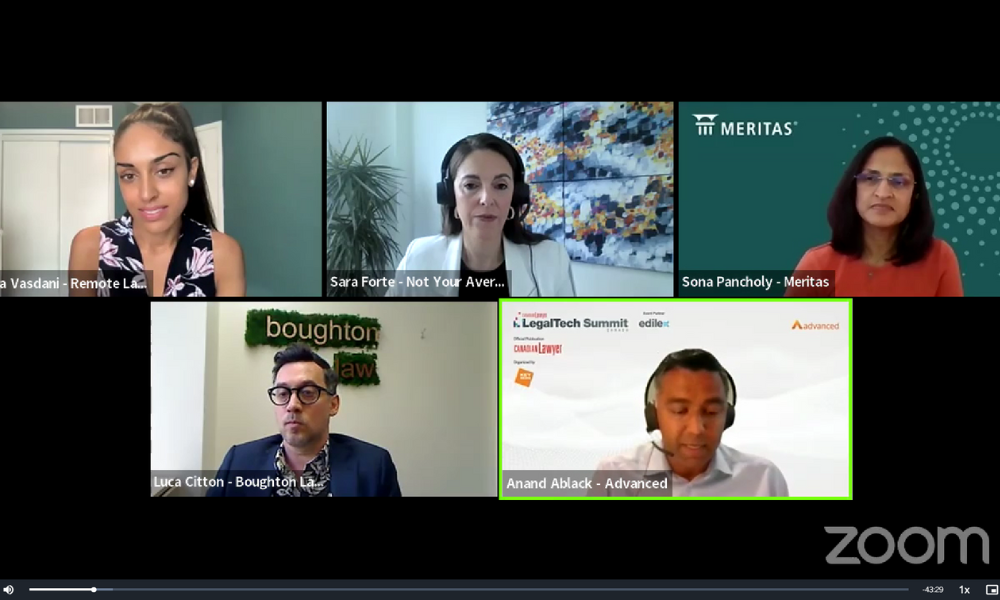

Moderated by Anand Ablack, vice-president of the North American Legal Markets at Advanced, panel members explored the effects of the great resignation, the cultural shifts created and how it changed lawyers’ new priorities. The roundtable also focused on the role of technology in the future of law firms.

Sara Forte, labour and employment lawyer and the founder of Forte Workplace Law, said the COVID-19 pandemic had a major impact on the great resignation as lawyers suddenly faced a bunch of nonnegotiable competing demands. For example, pulling elderly parents out of care homes and having kids attend school from home.

“Some law firms handled that very well and others didn’t,” Forte said.

Lawyers who had some time during the pandemic that getting to know themselves and their families and in connecting with other parts of their lives that they set aside, realized that the firm they worked for did not reflect or share their values and searched for a more value-centred approach, Forte said.

Some lawyers also found that their wellness and productivity are better suited to working remotely and they did not want compromise that. Forte said that with firms looking to bring people back to the office, a significant tension around resignation is about working from home.

She said it is crucial to examine the employees’ companies are losing to the great resignation from a diversity and inclusion lens.

“Are we rebuilding a traditional workforce that is excluding underrepresented groups from the law?” she asks. “I’ve been reading stories about people of colour who frankly feel safer working at home because they aren’t experiencing the same kind of microaggressions they did at the office. So, all of that is part of the big picture.”

Luca Citton, president of Boughton Law, said that for most law firms, the last two years have proven to be their most lucrative financial years and that the excessive work put much pressure on recruiting and retention. As a result, many firms spent a substantial part of their day recruiting employees and dealing with retention issues.

Most downtown Vancouver firms started throwing money at their associates in the hope that this would keep everyone happy and keep them, which caused pressure on small and mid-sized firms, who could not compete on the salaries as the national firms did. However, Citton says it caused smaller firms to reassess workplace culture.

“We realized that if we couldn’t compete on compensation, we had to come up with other offerings to keep associates, and it forced a lot of us to re-evaluate how when a candidate comes in, ‘how do I [differentiate] my office from a similar office? And on our end, what we doubled down on was mentorship.”

Teaching lawyers about the business of law, understanding profitability, what makes a commodity, and how to sell in the marketplace is something that most lawyers do not get in law school, Citton said.

Sona Pancholy, president of Meritas, the global alliance of independent law firms, said the pandemic reduced the barrier between lawyers in different ways. For example, partners sought more assistance from associates in delivering a service because they were unfamiliar with the technology.

“That automatically allowed them to work more collaboratively and look at each other as bringing value to the table in their ability to deliver services, and some of those things will continue to play out as firms explore what the next phase will be for them.”

Pancholy said the viability of the four-day work week is still a question as Canadian law firms continue experimenting to see the best working model for employees.

Principal lawyer and founder of Remote Law Canada, Tara Vasdani, said her approach to building and operating a hybrid or remote law firm has also been through technology.

COVID propelled the use of legal tech and made it a staple in any law firm looking to survive the pandemic and operate well, Vasdani said.

With companies like Alexei on the market, law firms can use artificial intelligence for legal research, and tech has permitted lawyers to operate remotely or on a hybrid or flexible model.

Vasdani said she created her law firm based on a fascination with how employment legislation or the common law deals with flexible employees, which can become complicated when dealing with a digital nomad. She receives questions from managing partners on the role of law students if law firms use AI for legal processes, and she says law firms can employ students for billable work.

She says her law firm assists organizations with avoiding some common pitfalls associated with having employees work remotely, such as not having an effective remote work policy.

“I think about how law firms will move forward, and my perspective was always that you must meet the clients where they are. So if clients are used to efficient and on-demand services, implementing these technologies into your practice to create that landscape will make your law firm, much more accessible and potentially a better place to work.”

Citton said the great resignation had given employees much bargaining power. However, should a recession hit, there would be a switch in how decisions are made and would go beyond the employee’s needs.

He said law firms could have a competitive advantage by focusing on ESG as a social innovation angle. “We’ll need to embrace going forward to keep an advantage.”

Vasdani said a recession would affect an entire business beyond its employees because the general consumer can no longer afford the legal services. As a result, she said companies would have to rethink their profits, and tech would be handling more of the legal processes.

Forte, who is also the chief happiness officer for Not Your Average Law Job, an online project shining a light on happy lawyers and their legal practices, said she spent much time as the head of a law firm thinking about if it was her job to keep ensuring that her employees are happy.

“I used to think that’s not your job as someone running a workplace, but if people are happy, they’re going to stay, and they’re going to be well, and if people are well, they’re going to be productive.”

Forte said that firms of all sizes would have to consider giving lawyers autonomy, the skills to design their careers, and the flexibility to build something that suits them and their life to stay connected. She says if lawyers cling to traditional ways that do not work for them, it is not promoting happiness.

Pancholy said different talents are coming into law firms for the first time. For example, client relationship officers are helping firms think about how to work and collaborate with clients.

“It is about diving deeply and thinking about what else the firm needs to spend time focusing on as they look for how they’re going to be more competitive, and the social aspect is a key part of it.”