Central bank rate should settle at three percent, say strategic advisers David Dodge, Serge Dupont

The health of the Canadian economy will largely depend on the response of wages and prices to the rapid tightening of monetary policy that began in the first quarter of 2022, Bennett Jones strategic advisers say in their report “Fall 2022 Economic Outlook – Managing Risks and Taking Action.”

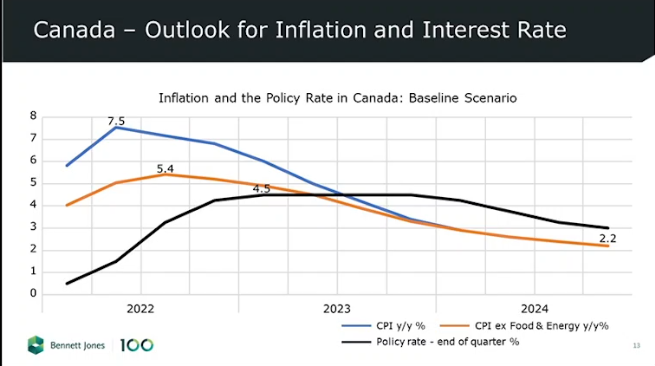

“Our assessment is that wages and prices are likely to respond fairly smoothly to the reductions in domestic demand caused by higher interest rates,” the report says. “Inflationary pressures should begin to abate early in 2023, and central banks should be able to halt policy interest rate increases.”

Earlier this week, the Bank of Canada raised the bank rate by 50 basis points to 4.25 percent but signalled that it might be finished raising rates, depending on economic conditions. The Bennett Jones report suggests rates could peak at 4.5 percent in Canada and 5.25 percent in the United States.

The report notes the global economy is slowing down as supply constraints, a war against Ukraine, sanctions against Russia and tension in the international trade environment are pushing up prices and interest rates. “Uncertainty is pervasive, from the price of commodities to the effects of zero-COVID policy in China. Global GDP growth will likely be in the three percent range for the next few years.”

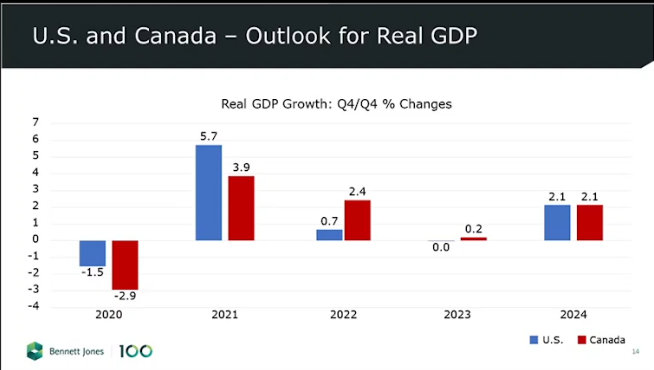

At a Thursday webinar presentation, Bennett Jones strategic advisers David Dodge and Serge Dupont predicted the US economy will undergo a “shallow recession” in the first three quarters of 2023. However, Canada would perform marginally better, helped by relatively high resource prices, with oil in the range of US$70-85 per barrel.

Dodge – a former head of the Bank of Canada – added the central bank would have to assess whether rates will have to be further raised. He said that that would depend on how “sticky” prices and wages are, meaning how long it would take the hikes to have the desired effect on inflation.

Dodge said he is generally optimistic that prices and wages will respond to the interest rate hikes. However, if prices are stickier and fail to react quickly enough, central banks “will need to tighten further.” This development could “precipitate a recession in 2023 that could be pronounced, with knock-on effects,” including the impact on the fiscal position of governments.

“This is why it is appropriate that central banks continue to affirm their strong intent to tame inflation and that governments complement monetary policy by moderating spending.”

Dodge noted that renowned US economist Larry Summers, a former United States Secretary of the Treasury, has taken a more pessimistic view, suggesting that in the past, it took longer for interest rate hikes to have their desired effects on inflation.

“That is a very respected view,” he said. “But I think the view we’ve taken is that price expectations are more firmly anchored today than the last century, and even the first ten years of this century,” with prices and wages more reactive to interest rate hikes.

Dodge also suggested that the two economies would be growing at a rate of about two percent during 2024 and that in both the United States and Canada, by the end of 2024, inflation should come down to close to the two percent target, and the headline interest rate would drop to about three percent.

The report, aimed at informing businesses on public policy issues, suggests that the private sector and governments must work together to “address gaps, grow our productive capacity and expand our ability to produce the goods and services that the world wants to buy.” This collaboration requires a policy framework that “supports confidence and incites private investment, while also strengthening global partnerships and market access.”

It also suggests that such investment must be “much higher than in recent years,” estimating the need for an added flow of public and private non-residential investment of about $80 billion per year. That is based on lifting investment to 17 percent of GDP, from 14.4 percent of GDP in 2022 and a historical average of 15.6 percent.

While Canada is exposed to global forces, contributing to inflation, “our economy does not yet feel like one that is slowing down,” the report says. There is still excess demand, labour markets remain tight with a low rate of unemployment and a shortage of workers, and profit margins are elevated.

The report says the Canadian economy is in “a better place at this juncture than other developed economies” thanks to its strong energy exports. In the second quarter of this year, while the U.S. energy trade was roughly in balance, Canada realized a surplus of over 6 percent of GDP, while the euro area incurred a deficit of more than four percent of GDP.

Canada’s energy advantage in a period of high prices represents a flow of revenue that is growing national income. In the first three quarters of 2022, real national income rose at an annual rate of three percent in Canada, compared with 0.2 percent in the United States. Resource-producing provinces, like Alberta, Newfoundland, and Labrador, also have large fiscal surpluses.

However, Dupont, who held many federal government positions, including Deputy Clerk of the Privy Council and Deputy Minister of Intergovernmental Affairs before joining Bennett Jones in 2018, said that business has to rise to the challenge of navigating through an uncertain future.

“As a former public servant, I’ve never been particularly keen on telling private sector leaders how to run their business. I have a sense that they’re generally pretty good at it,” he said. But the world is changing, which may require a response to the existing structural trends.

“But with every crisis, with every basic transformation, there are opportunities or new markets being created,” he said. “So, it’s really important that corporations . . . think about and being agile and being able to be responsive and to do the pivots that are necessary.”