JCAP works to bring bad behaviour to the attention of securities regulators and investors

In 2022, Cobre Panama, an open-pit mining operation located 120 kilometres west of Panama City, Panama, milled 86.145 million tonnes of ore, recovering 350,438 tonnes of copper, 139,751 ounces of gold and 2.8 million ounces of silver. This year, in Q3, copper production alone hit 112,734 tonnes, but Q4 is likely to produce a very different result for the mine’s owner, First Quantum Minerals, a Toronto-based company listed on the TSX.

This week, Panama’s Supreme Court ruled that the contract that allowed mining at the site was unconstitutional. The decision comes on the heels of the company being forced to suspend operations last week. The closure wasn’t due to depressed mineral prices or a mined-out resource but a blockade of the Punta Rincón port by protestors in small boats who managed to halt the delivery of coal necessary to keep the mine’s power plant running. The protestors object to the presence of the mine, the original granting of permits to open the mine and the way licences to operate the mine continue to be granted. Two people who were protesting along a highway leading to the mine were shot to death earlier this month. There is even a possibility Panama will hold a national referendum about the mine.

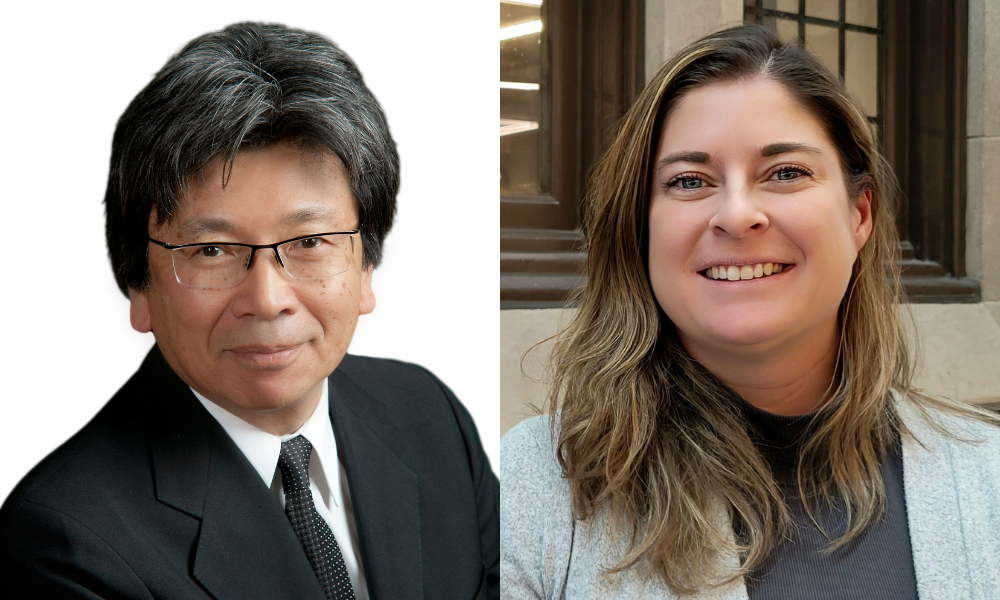

Violence, death, massive protests and political struggles may not be common aspects of doing business in Canada, but that doesn’t mean they are unknown situations to Canadian companies engaged in mining activities around the world. They also aren’t unfamiliar scenarios to the lawyers and law students behind Osgoode’s Justice and Corporate Accountability Project (JCAP). In fact, JCAP was created about a decade ago to investigate exactly these types of conflicts between Canadian mining companies and the people who live in and near areas of mining activity, such as local Indigenous populations who often have very few means of standing up and objecting to exploration and mining activities, according to Shin Imai, professor emeritus at Osgoode, and a member of the board of directors of JCAP.

“It started because I was interested in Indigenous rights. I began doing some work in Latin America, and I discovered Canadian mining companies were a big issue there. This was a big surprise to me, that there was so much conflict around these mines, so I started looking into them, and the allegations, in some cases, were extremely serious and very upsetting.” Imai then assembled some law students and began investigating what was actually happening at mining sites and what they could do to help.

Running investigations into mining companies and their activities is not something that has won Imai or any of the project’s participants friends in the mining industry. He says that they are often accused of being against mining, but that isn’t true.

“I say, ‘just because I’m against drunk driving doesn’t mean I’m against driving.’ It’s like the 401 or any major highway, just having a voluntary code for all the drivers with no enforcement. That wouldn’t work. It doesn’t work in the mining industry either.”

Holding companies to account has taken on a few different avenues. JCAP began by compiling reports of human rights abuses (including murder and gang rapes) and presenting the information to bodies such as the United Nations and the Organization of American States, but that route didn’t produce the results the project was hoping to achieve. International political bodies don’t regulate companies, so the companies didn’t care. Giving reports to countries that host troubled mining projects also didn’t work because the miners were either invited by the countries or the miners operated with the blessing of governments and government officials.

“These companies take advantage of really weak governance and corrupt governments,” says Lisa Rankin, a JCAP research assistant and a second-year law student at Osgoode. Rankin is a mature student from Nova Scotia who worked in Guatemala as the director of programs for Maritimes-Guatemala Breaking the Silence Network, an organization developed to support the efforts of Guatemalans struggling for political, social, and economic justice. Her experiences in that role are what drove her to apply to Osgoode, as she wanted to be a part of JCAP.

To illustrate how problematic mining companies operate, she gives the example of the Escobal silver mine in Guatemala, which is owned by the Canadian company Pan American Silver. Goldcorp, a Toronto-based company, originally discovered the deposit, and agreed to sell it to Tahoe Resources, another Canadian company, in 2010. In 2019, Pan American bought Tahoe for over $1 billion.

According to Rankin, the project drew peaceful resistance from the local community right from the start, including a local referendum. Eventually, protests were set up in front of the mine entrance. “Mine security opened fire and shot seven men… There was ample evidence of the mine security officer being supported, following the attack, by Tahoe Resources,” she says. A court case was filed in British Columbia, Garcia v. Tahoe Resources, but as that was progressing through the courts, the company was sold, largely because the protests continued and because the country’s constitutional court issued a ruling shutting down the mine, suspending its operations and ordering the company to consult with the local Indigenous community – a process that is still ongoing.

Tahoe seemed to be acting in accordance with the law. “Permits for the Tahoe project were given and then, a couple of years later, the person who issued them is now on the run from the law for corruption,” says Rankin.

“We’ve heard of bribes of government officials. Permits are being pushed forward without the consent of communities by corrupt governments. That’s such a key part of the findings [of investigations] by JCAP into these companies.”

Tahoe also gave the impression that everything was running smoothly at its operations and that there were no protests or upset local residents or Indigenous communities. That’s what its shareholders heard.

Wanting to find a better way to make a difference, JCAP switched its tactics. Now, the project has securities regulators and investors in its sights.

“We bring complaints to securities regulators when companies don’t disclose social conflict or when they don’t disclose lack of Indigenous consent,” says Imai, noting that to date, the project has filed approximately ten complaints. Included in that group are complaints about the Tahoe mine.

Imai explains that the project goes beyond simply filing complaints because that just sends them into the securities regulator’s “black hole.” JCAP also publicizes its findings, which has proven to be a successful approach.

“We looked at six of our cases. We found that when we publicize [the complaint], it gets picked up by the mining press, and the stock prices fall. In one case, we did not publicize it, and the stock price didn’t fall,” says Imai.

He adds that not every investor cares about companies that break their social, environmental and governance responsibilities, but enough do. Some investors are afraid of losing their investment or “don’t want to invest in anything that makes them vomit,” and their actions can influence how companies behave. This is especially true when large institutional investors divest due to a company’s actions.

After making the situation at Tahoe public, Imai says the Canadian Pension Plan, a pension plan in Denmark and another in Norway divested. “The Norwegian one was very direct about why they were withdrawing.” Once that happened, he said the company’s stock price dropped. “The retail investors, they are just looking at publicity material on the company’s website. They’re the ones that got screwed when Tahoe went down from $25 to $5. The pension plans were already out of it. There was just a bunch of retail investors stuck with Tahoe saying, ‘communities love us, and there’s no merit to the court case, and everything is hunky dory.’”

Imai strongly believes that regulators should be doing more and paying more attention to corporate social responsibility issues. It was the lack of reporting on these issues that drove Tahoe’s investors to file class-action lawsuits against the company, claiming it wasn’t reporting the problems that would eventually depress the stock price. In Canada, that class action was settled in Ontario for US$13.5 million in July. In the US, the settlement was US$19.5 million.

“The whole point of securities regulators is they’re supposed to protect investors, but they’re stuck in this kind of rigidity, with their heads in the sand trying to pretend there is nothing happening in the world around them, when, in fact, the world around them is closing down mines. Or like First Quantum. They lost 40 percent of their value,” he says.

“The question is, how much did First Quantum really, really tell their investors about what is happening in Panama? Because they’re down there. They knew. I find it surprising that if investors knew about the real seriousness of the protest, why would the prices fall 40 percent? It falls 40 percent because people get news they didn’t know about, and then they think, ‘Oh my God, I’m getting out of here.’”

Even as he considers investors fleeing from mining companies, Shin is at the stage where he is contemplating his own eventual departure from JCAP. The project has a board of directors of six volunteers that manage its operations and oversee the students and the research, and Shin describes them as “all much younger” than he is.

As for the students, he says one of the great things about working at a law school is that he can teach students techniques and train them how to use the Securities Act, apply it to certain contexts and bring about even greater accountability to the mining industry. The project pays the students working for it – typically, they number between two and six per year. Some of JCAP’s funding comes from the Nathanson Centre on Transnational Human Rights, Crime and Security at Osgoode, but the organization isn’t typically top of the list for other funding sources due, Shin says, to its small size and to the quiet and low-key way it operates. “I think we’re kind of invisible to that world,” he says.

“If we get an angel investor, I would be so happy because I’m trying to retire.”